We took a tour of the historic Monroe St. Abbey in downtown Phoenix. Here’s what we learned, plus lots of photos showing you what it’s like inside.

This story was first published in The Copper Courier’s daily newsletter. Sign up here.

On Día de Los Muertos weekend, I received a last-minute invitation from a friend to the SOULS festival. The event was great, but the real reason I wanted to go was to check out the venue: the Monroe St. Abbey.

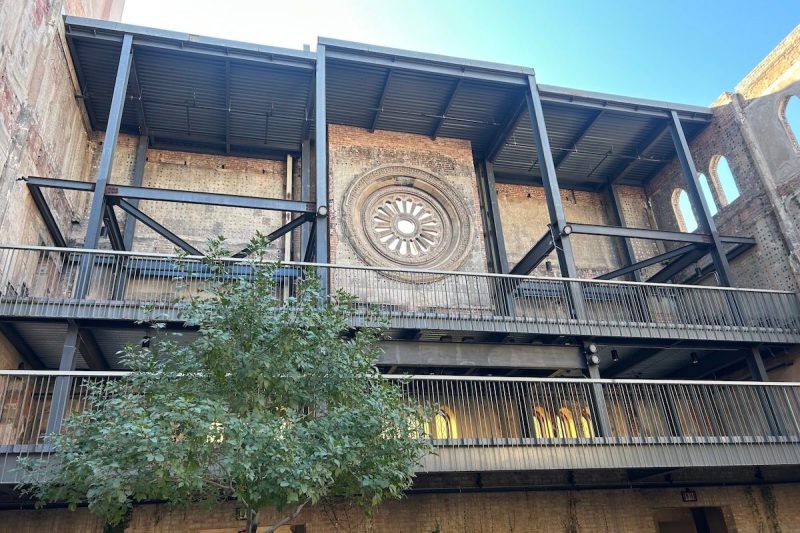

I have walked past this building many times over the last decade and always admired its beautiful exterior and stunning rose window. I knew that, though it stood empty for a long time, it had reopened recently and was hosting weddings—and this festival was the first chance I’d gotten to see inside.

I was floored by the unexpected garden inside, and the way that parts of it were kept in ruin while others were modernized. It was a fascinating setting I hadn’t experienced since I attended a film screening at a Romanian castle—and I certainly never expected to relive that here in Phoenix.

After I wrote about my experience in this newsletter, I was contacted by Jones Studio, the architecture firm that brought the abbey back to life. They offered me a tour so I could see the full 28,000-square-foot building.

Here’s part of that commentary from Eddie Jones, the firm’s founder and principal, edited for length and clarity:

“This [structure] was built in 1929 for the congregation of the First Baptist Church of Phoenix. The congregation built that giant mega church on Bethany Home and Central and moved there. And then this had a few owners here and there, but then it became abandoned.

“And then in ’84 it caught fire. Vagrants had built a campfire. That’s what happens when you leave buildings empty, and this entire roof burned and came crashing down. This interior space was suddenly an exterior space, and it’s stayed that way to this day.

“Roofs perform a structural [function] besides keeping the rain off your head—they structurally or laterally brace the surrounding walls. But once you don’t have a roof, then this [front] wall in particular was leaning and in danger of collapsing.

“The city of Phoenix condemned the building and said it’s got to be demolished. Terry Goddard, who was [Phoenix] mayor and attorney general for the state of Arizona, loves history, and he couldn’t bear to see this historic building torn down. So he bought it, and then he temporarily stabilized that wall.

“Phoenix approved it, thinking it’d be a year or two [until it was fixed]. It was more like 20 years, and then it started to fail again. But Terry, he had a dream that this could be something special.”

Jones and some architect friends of his had a hero: Herb Greene, who created an urban theory called Armature. This is the idea that, in Jones’ words, “older buildings can become armatures for public art, and the community actually uses these old buildings as a canvas.”

Phoenix does not have an example of this, Jones said, so he and his friends sought out a location that could work for this type of project. After spending a day searching downtown and only finding disappointment, landscape architect Chris Winters showed the group the First Baptist Church.

“I peered through the cracks, and I could see that nature had planted a garden in here,” Jones recalled. “She will always do that. And she was taking back her property. And I go, ‘Oh, this is it. This is it.’

“And so I don’t even think Terry Goddard knew who we were. We decided to put together a proposal that basically said we will work pro bono, helping you create a plan that you can then take to the bank and apply for tax credits. And once you get the money, then you know we’ll be on the clock under one condition, that this has to remain an outside garden. He says, OK.

“Now, that was 2011. It’s close to 2026 now. That just shows you what a labor of love it was for everybody involved. And in this day and age, maybe that’s a rare occurrence. But how can you not fall in love with this? Everybody hung in there with smiles on their faces, just knowing the potential was worth the patience.”

One of the first things the team had to do was stabilize the building. The outer wall was unreinforced brick, and it was leaning. A steel structure was added to brace the wall, while also functioning as a viewing space for people to look down into the courtyard. “We turned a pragmatic approach into something very functional and necessary,” Jones said.

“There’s a video of time-lapse photography, and it shows the contractor with this big ass crane out there on Second Avenue lifting another big ass crane over that wall and setting it in here, and taking a smaller crane, lifting it over the wall, setting it in here.

“Then the contractor cut holes in the floor, poured new footings, cut holes in the second floor, cut holes in the third floor, cut holes in the fourth floor, and took these very large steel I-beams and dropped it down all the way to the ground, to the footing, and then bolted the walls, braced them back to those new columns.

“That’s something. That’s surgical intervention. And so once the building was stable, that changed everything. The banks paid more attention. The city of Phoenix knew we were serious and … they bent over backwards to make this happen.

“When people that are in the arts community come in here … their jaws would drop and they’d go, ‘Don’t change anything.’ Got it. Next person, vocalist, beautiful reverberation, ‘don’t change anything.’ OK. And so basically we didn’t, and I’m always amazed at how these people [are] inspired. The building gets used in so many different ways that we never even imagined, and that is a metric of success.”

While the abbey is currently hosting weddings and other events, there are plans in the works to bring in dining and a speakeasy to open up the building further to the public. We’ll continue to follow the developments as they come!